Friday Notes, November 12, 2021

Dear Friends —

A 16-hour flight gives a person time to reflect on four weeks of travel — and to recover from a sprint through the massive Johannesburg airport to get to said flight. (After a month away, you’re not going to let a late connecting flight stop you from getting home.)

I’ve been with colleagues in New York, Kenya, and Zambia, meeting in person after many, many months of remote work. We talked through near-term decisions, made plans for 2022, got to know one another in unstructured conversation, and laughed a lot. Bleary-eyed from the long flight and still six hours from home, I am already thinking about when I can travel again.

I learned a lot that’s IDinsight-specific, but here are a few somewhat disconnected reflections that may apply more broadly:

Leaders need to explain themselves, often and clearly: At a team meeting in Lusaka last week, I offered remarks about how I see much of my job as making tradeoffs between what would be optimal for an individual team member, project team, region, or function, on the one hand, and what is best for the organization as a whole, on the other. Considering tradeoffs, weighing costs and benefits, and thinking across levels and over time is easiest to understand through specific examples, so I walked through my thinking about several types of decisions that affect the work-life in the Zambia office. These included how much emphasis to place on partnerships with governments vs NGOs, whether to assign team members to work on the same project for a long time or encourage moving around to new opportunities and when and how to build out the capacity of support functions without blowing up our overhead. For each, I tried to give a picture of the factors that were being weighed, and to offer a strategic view – at the organizational mission level, over the medium- to long term.

What I learned from the very positive response is how much people appreciate visibility into what goes into the deliberative process that they don’t take part in directly. And how easy it is for incorrect narratives to fill an information vacuum. Clear, honest explanation helps answer the question team members may have: "Why isn't leadership doing X, because X is so obviously the thing to do?" It shows respect for team members’ maturity and their own commitment to the organizational mission. Leaders need to explain themselves. I will be doing it more.

Global citizenship is a global aspiration: One of the most eye-opening conversations I had on this trip was with a Malawian colleague who, along with two compatriots, is working on a long-term project in their home country. The ability to communicate clearly and build relationships, the understanding about what’s really going on, the ease with which people who deeply know the context manage practical aspects like meeting protocol — all that and more adds tremendously to our ability to have social impact through our work.

But my colleague wants to work in other countries. In fact, he said he joined an international organization in part because of the opportunities in a variety of settings, to have the personally and professionally rewarding experience of being a welcome outsider. Just like his peers at IDinsight from the Americas, Europe, East Asia, and other regions where we don’t have project work.

The penny dropped. Although I’ve had a long-term vision of IDinsight as a place where all team members have a lot of opportunities to work on projects in countries other than their own, I hadn’t quite recognized the tension with focusing on “local grounding” — assigning people based on nationality. (It’s blindingly obvious, but I just hadn’t confronted it before my young colleague placed it on the table.)

This is one of those trade-offs I mentioned, now very much in the forefront of my consciousness. I’m aware that I need to be able to explain where we land with staffing projects, factoring in the global citizenship aspirations of team members. I am also aware that other international non-profit organizations that are making progress toward inclusive hiring practices ought to be thinking about the same.

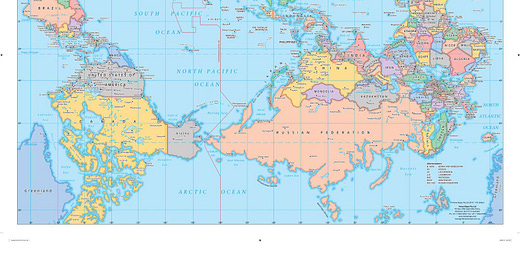

Time zones are power zones: San Francisco is 11 hours behind Nairobi and 10 hours behind Lusaka. That means there is virtually no overlap in a normal workday. Phone calls and video conferences require someone to get up early or work late. Asynchronous communication over Slack or email feels telegraph-speed rather than internet-speed unless someone is checking incoming messages long after a proper workday.

I experience this daily when I’m home, because my meetings start at 6 a.m. (sometimes earlier), are dense through the morning, and pick up again after dark. I’ve considered it a fact of life in an international NGO. On this trip, though, I heard frequently how disruptive the time zone challenge is — and how much the mundane task of scheduling becomes a daily reminder of social and organizational hierarchy.

We cannot modify the space-time continuum. But I’m thinking hard about the pros and cons of establishing organization-wide norms about how to manage – or at least negotiate – the time zone tension. If we do enforce scheduling norms, I will definitely have some explaining to do.

Upon arriving at Newark Airport, I was welcomed by one of the dumbest signs I’ve ever seen. “Especially to China” ?!? A country of 1.4 billion people that has experienced something like 1/12th the cumulative COVID cases as New Jersey (population 8.8 million)?!? Unbelievable.

Have a good weekend – and safe travels if you’re traveling or have traveled, especially to New Jersey.

- Ruth