Friday Notes, June 13, 2025

Dear Friends -

If I had to list the top 10 things I love to do, somewhere on the list would be spending time with people who are absolutely passionate about the value of creating sound public policy by using data, empirical research, and theory. I wouldn’t necessarily rank it higher than baking French pastries or taking a long walk with a friend, but it would definitely be on the list.

This week I got to do just that by participating in the Public Solutions R&D meeting, convened by Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. You might think the Kennedy School would have something more pressing to think about, given the termination of Federal funding, restrictions on international student visas, and hefty tax on endowments. (My thought upon receiving the invitation: “Don’t you-all have enough on your hands without hosting a bunch of wonky nerds and nerdy wonks?”) But convene we did — not in spite of the assaults but because of them.

Universities are being attacked by people in power, and there is relatively little public outcry. This is not because they do too much life-saving medical research or invent too many new technological marvels. It is also not because they are hotbeds of antisemitism or technology transfer to the Chinese Communist Party. Universities are being attacked because there has been a successful campaign to characterize universities as incubating and indoctrinating the young with “woke” ideas about equity, justice, identity, and more. In their admissions process, hiring, curriculum design, and incentives for promotion and prestige they are seen as elevating a narrow set of ideologies and crowding out alternative viewpoints. (For a short course on this perspective, check out this interview with Chris Rufo, architect of the current assault on higher education.) While there is a lot of collateral damage, the primary targets of all the defunding, demonizing, and delegitimizing are the humanities and the social sciences.

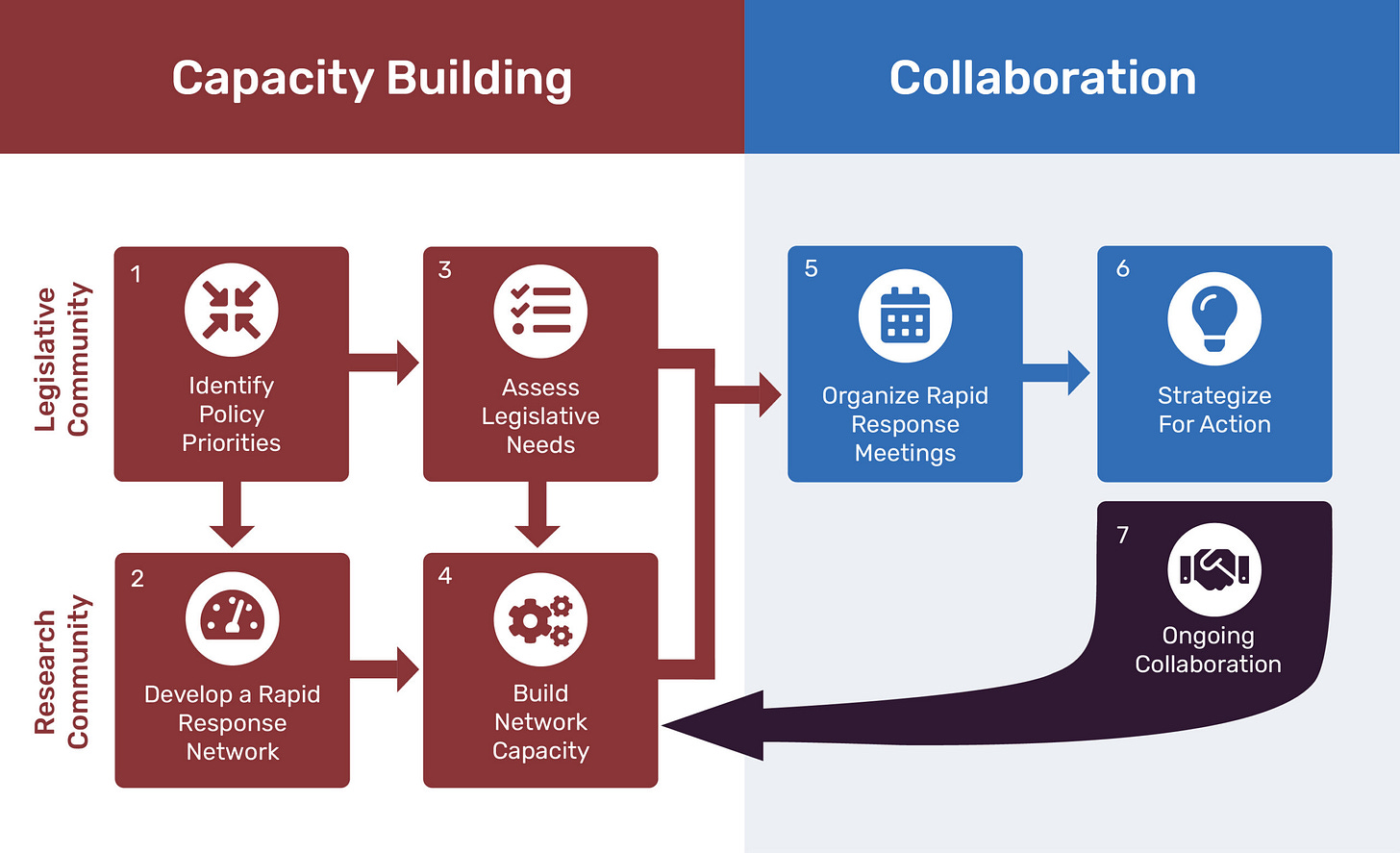

Against this backdrop, the people in the meeting room at the Kennedy School were trying to find the opportunity in the crisis. If universities have to reinvent themselves in this changed context, is this a moment for both creating and demonstrating greater social value? They were constructing a theory of change that I heard as something like this: If we can learn from experience how to apply academically sound concepts and methods to real-world problems . . . and if we can be good, reliable partners in solution-finding to both policymakers and communities that are the most affected by failing systems . . . and if our institution can be a supportive home base . . . then we can contribute to meaningful improvements in many people’s lives (like our colleagues in the biomedical sciences do) . . . and the relevance and importance of our work will be recognized and thrive.

There are proofs of concept for these “ifs.”

Can academically sound concepts and methods be applied to real-world problems? Far from ideologues or theoreticians, people who do the type of work we were discussing at the meeting are deeply committed to empirical social science and had lots of hard-won experience to share. They like to count, to test by comparing “treatment” and “control” groups, to adhere to “correlation isn’t causation” as a talisman of truth. While they might turn to regression models in a pinch, most would far rather observe than assume or extrapolate. Even when observing requires hard-to-come-by time, money, patience, and ingenuity.

There are many, many examples of real-world applications, both for incremental policy tweaks and for big, bold, new ideas. Among other examples, we heard about Harvard’s Opportunity Initiative’s successful efforts to increase the effectiveness of affordable housing vouchers and the application of the University of Chicago Crime Lab’s research to reduce gun violence.

Can academics be good and reliable partners in solution-finding to both policymakers and communities? Many participants spoke of painstaking work to build enduring relationships, often at the local level, and emphasized the importance of entering with humility and a service orientation. For instance, the Stanford University Reg Lab responded to a challenge faced by municipal bureaucrats by building an AI-powered tool that has dramatically reduced the paperwork burden in San Francisco government. A Harvard researcher worked with sheriffs from around the country and a nonprofit organization to test accreditation of prison health services as a way to reduce the shockingly high death rate among incarcerated people. And the University of California Berkeley Possibility Lab is exploring a whole array of models to engage community members in providing input and feedback around policy initiatives.

Can a university be a supportive home base for public solutions R&D? While many academics at the meeting spoke about the tension between the applied work they do and the type of research and products valued by their institutions, there are signs of progress. The Pew Charitable Trust has documented examples from universities across the country that are taking steps in the right direction — for example, by broadening their promotion and tenure systems to recognize the value of social impact research. The proliferation of “labs” within relatively well-resourced institutions is a sign of interest among faculty and leadership. And the W.T. Grant Foundation is trying to encourage movement in the right direction by generating evidence, creating resources, and offering incentives in the form of institutional challenge grants for research-practice partnerships.

As universities face the prospect of less funding and more challenges to their legitimacy, they will need to create a fundamentally new value proposition. In the midst of crisis, there is an imperative for them to reimagine their role — and the people in that meeting definitely had ideas about how to do just that.

Now for something completely different: my hummingbird feeder, and the feeders that lots of other Californians hang up in their backyard, are affecting evolutionary change in the birds. What?!? Thanks to research by a clever and curious UC Berkeley graduate student, Nicholas Alexandre, we now know that the increasing use of bird feeders over time is strongly associated with both the expansion of the range of hummingbirds and, get this, with growing longer beaks. That is a remarkable finding — and much more welcome evidence of the Anthropocene than the collapsing glacier.

Have a good weekend.

-Ruth