Friday Notes, February 11, 2022

Dear Friends —

Have you seen the movie Queen of Katwe? Directed by Mira Nair, the 2016 film tells the story of Phiona Mutesi, a girl born into one of Kampala’s largest slums who is introduced to chess at age 9. She quickly demonstrates the talent to win national and regional championships, breaking gender and class stereotypes with every checkmate. It’s a beautiful movie, showing a far more authentic reality than most films set in Africa — gritty, noisy, complex, alive — and embuing that reality with a sense of possibility. Based on real events, the film shows Phiona besting the neighborhood boys at chess, persisting in school, and being encouraged by her coach to see her horizons as unlimited. It’s a master class in asset framing. (The trailer will give you a sense.)

Phiona is at once ordinary and very special. The actress who plays the role looks and speaks like a Ugandan girl from a humble background; her surroundings are familiar to anyone who has seen urban poverty. She is like every other Ugandan girl who will likely not make it through secondary school, and who could barely imagine going to university. But she is also manifestly special because chess competitions have shown a light on her intellectual gifts.

Could seeing someone like Phiona help other young people imagine what’s possible for them — and in the process make it possible for them? That was, more or less, the question that economist Emma Riley asked when she began a research project in 2016. The study participants were Ugandan teenagers; the movie was the treatment; the outcomes were exam scores and academic progress. And the results: eye-opening.

Here are the specifics from the paper forthcoming in The Review of Economics and Statistics (ungated working paper here): Riley identified 1,500 Ugandan secondary school students who had taken a mock version of a high-stakes national exam, and were on the verge of taking the real exam. Assigning them randomly, she screened Queen of Katwe for one group of students and a “placebo movie,” Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children, for other students.

In research like this, the way you allocate people to treatment and placebo groups often takes logistical creativity, and this study was no exception. Here’s what Riley did:

Students were individually randomised into the treatment or placebo movie upon arrival at the cinema . . . This was done by students lining up outside the cinema and one by one entering, upon which an assistant picked a ticket out of a bag without looking and handed it to the student. The bag was opaque and the tickets identical except for the name of the movie printed in small print at the bottom of the ticket. An assistant was chosen to actually pick the ticket to further reduce any probability that a student might try and pick a particular ticket.

Immediately after getting a ticket, students went to the designated registration desk for that movie, before proceeding into the theatre. Students with tickets for different movies were kept separate the entire time, even using different bathrooms.

With whatever they took from the movies in their heads, all the students soon after took the national exam. Riley obtained their scores, and over the years that followed was able to trace whether they applied to and were admitted into a university.

It may seem a little crazy to think that exposure to one movie could make a difference in something as important as passing a high-stakes exam or pursuing higher education. But to these young people, it did.

I find that treatment with the role-model movie leads to lower secondary school students being less likely to fail their maths exam a week later: 85% of those who watched Queen of Katwe passed the exam, whereas only 73% of those who didn’t passed. This effect is strongest for female and lower ability students. For upper secondary school students, treatment with Queen of Katwe 1 month before their exams results in an increase in their total exam score of 0.13 standard deviations. Effects of treatment are strongest for female students in the compulsory mathematics paper. In both classes, female treated students are more likely to remain in education in subsequent years, closing the gender gap with their male peers.

The plain language translation: Girls who did badly on the mock exams and then sat in a theater for two hours watching a movie with a positive role model ended up doing a lot better on the real exam a month later. Girls who saw the movie that featured a someone very much like them being a brainiac did particularly well in math. And somehow the effect persisted, so that more of them ended up going to university than would typically have been the case.

This research is consistent with a lot of studies in social psychology on the effects of exposure to “counterstereotypical” role models (some summarized here). Even a brief glimpse of a woman doing a “man’s job” or a person from a marginalized community in a prominent leadership role can make a difference in individuals’ beliefs about what is possible. As Marian Wright Edelman once said, “You can’t be what you can’t see.” Correspondingly, you may be able to be what you can see.

Above and beyond whatever the research says about the potential for media interventions to affect educational outcomes, all of this should be a big nudge toward yet more attention to representation. It means that there’s a multiplier effect — maybe a really big multiplier effect — anytime we’re able to create space and visibility for people who are positive role models. There are a ton of reasons to focusing on diversity in leadership, and one of them is surely the opportunity to expand the appreciation for what’s possible until the rare becomes commonplace. (You may have noticed a lot of counterstereotypical images out on social media today, on the International Day of Women and Girls in Science.)

Queen of Katwe is a wonderful movie. Riley’s study is a fantastic contribution to the literature on the importance of representation. Together, they say something we need to hear about the power of the seeing and believing.

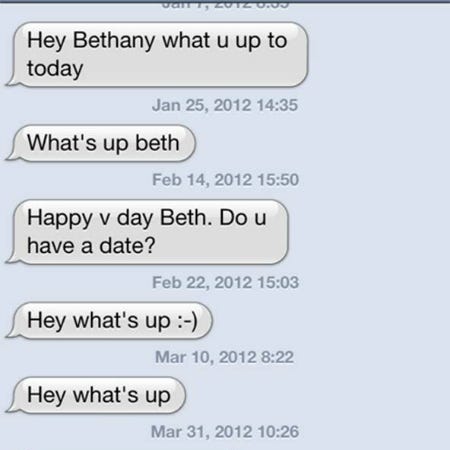

Of all the web-based services out there, a great one is making awkward moments in relationships better, one text at a time. Justine Ang Fonte offers up a curated set of templates to use when you need to can’t quite find your own words for “Get out of my life,” “I really screwed up,” or “Why the hell haven’t I heard from you after our last night together?” She’ll also write custom texts upon request.

On Instagram at @_good.byes_, Fonte (aka “Your Friendly Ghostwriter”) is a master of gentle yet clear messages. Here’s an example to send to someone who’s ghosting you:

Hi Vishal, I really enjoyed our first two dates and know you have a lot on your plate right now so, in an effort to honor the space you need, I’m going to let you lead. Know that I’d love to see you again and if the feeling is mutual, text me and we’ll make that third date happen. Either way, I’m thankful we met and wish you a Happy New Year.

Worth a look at the site, if only to see all the awful situations people get themselves into.

Some of the best advice I’ve ever read popped up on Twitter this week: Romeen Sheth’s 20 tips for people in the early stage of their careers. It’s all solid gold.

Have a good weekend,

-Ruth